10.09

Share ArticleHistory of tax havens and how they work today

It is hardly surprising that bank secrecy originated in Switzerland. The first known documents prohibiting bankers from disclosing information about their clients date back to the early 19th century. However, banking secrecy experienced its true heyday in the 1920s, when many European countries were forced to raise taxes to cover debts accumulated during World War I, and many wealthy Europeans sought ways to hide their capital.

Switzerland saw the benefit to the economy and, in 1930, cemented its reputation as a guardian of financial secrecy by making disclosure of financial information a crime. Today, however, the main euphemism for tax havens is the term “offshore,” which literally means “away from the coast,” even though Switzerland itself is located inland. Over time, island states such as the Maldives and the Caribbean became major tax havens. This made logistical sense: small island territories had little prospect of industry or agriculture, so financial services suited them.

The main reason for the emergence of offshore zones has a historical basis - it was the collapse of European colonial empires in the first decades after World War II. Britain was not prepared to directly subsidize Bermuda or the Virgin Islands, but encouraged them to develop a financial sector closely linked to the City of London. Nevertheless, the subsidies proved necessary, albeit in a disguised form, as a significant amount of tax revenue began to flow to the islands.

How taxes are avoided today

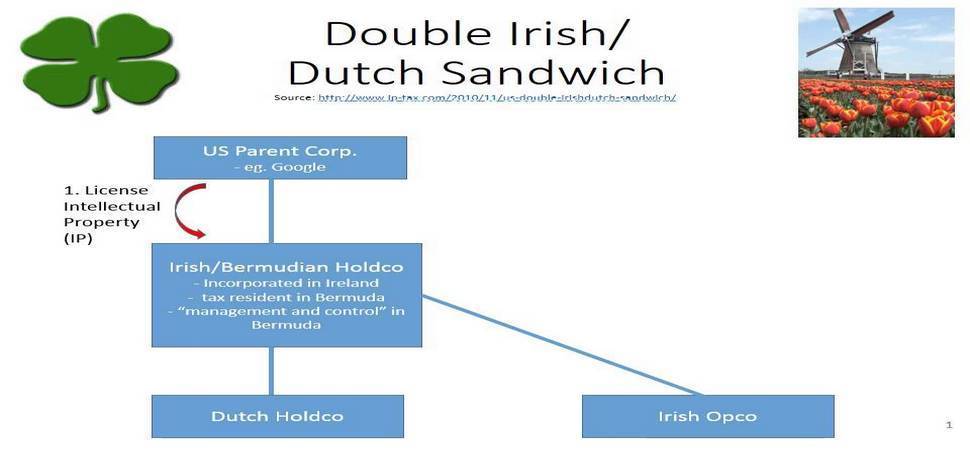

One possibility is the so-called “Irish-Dutch” scheme. Imagine that you are an American entrepreneur. You can register a company in one of the offshore zones and sell it your intellectual property rights.

That company opens a branch in Ireland. Then another Irish company is set up, which charges European companies amounts comparable to their profits. But that's not the end of the scheme - another company must be established in the Netherlands. The second Irish company transfers the funds to the Dutch company, which then transfers them back to the first Irish company, whose office is located abroad, such as in the Caribbean.

If this system seems confusing to you, that is its purpose. Compared to cross-border tax laws, two-part valuation looks like a model of simplicity. Tax havens thrive on the fact that tracking cash flows is difficult at best and virtually impossible at worst. Sophisticated tax systems allow multinational companies to significantly reduce their tax liabilities.

It is easy to understand people's dissatisfaction. Taxes are a kind of payment for membership in the state “club.” We believe it is unfair for someone to avoid paying dues while continuing to enjoy the benefits of this “club.”

However, tax havens have not always had negative connotations. In some cases, like other offshore centers, they acted as safe havens and helped persecuted people protect their assets. For example, Jews in Nazi Germany hid their capital in Swiss banks, which were known for their confidentiality. However, the reputation of Swiss bankers suffered considerably when, shortly thereafter, they began helping the Nazis hide their looted gold with the same zeal, refusing to return it to its rightful owners.

The contradictory nature of today's tax havens has to do with two main factors: tax avoidance and tax evasion. Tax minimization is perfectly legal because the rules apply to everyone. Small companies and even individuals can set up cross-border legal structures. However, the services of consultants who can competently set up such structures are expensive, and not everyone can afford them, since revenues must be high enough to justify the cost. Nevertheless, those who try to avoid paying taxes still find various ways to do so.

These include VAT refund fraud, wage envelopes and customs fraud. The British tax authorities believe that much of the under-collection of taxes is due to a lot of small-scale tax evasion, rather than large-scale fraud involving wealthy individuals and banks. However, this is difficult to say with absolute certainty, because if the scale of the problem could be measured accurately, it would not exist.

What can be done to combat tax havens?

There are a number of measures that can be taken to combat tax havens and help reduce tax evasion. First, international cooperation between countries could increase the transparency of financial flows, making it more difficult to hide income abroad. Second, introducing a global minimum tax on corporate profits would reduce the attractiveness of tax havens. Tightening the rules on tax returns and mandatory disclosure of companies' ultimate beneficiaries could also be an effective solution.

Fighting offshoring requires political will. In recent years, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has taken several initiatives in this direction, but so far they have not been very effective.

.webp)

Reviews